- Unravelling the Art of Stanley Spencer

Analytic attention to process is the British genius.

Hugh Kenner, A Sinking Island.

Stanley's

creative

impulse

For most artists the creative impulse

remains indefinable and the mental processes by which it becomes a

picture mysterious. In the evolution

of a painting the whirl of

ideas surfacing from

an artist's subconscious becomes

integrated into an entity (defined

here as a percept, concept, idea or emotion to which

the thinker mentally imparts form) which is almost

inexpressible in

words, so much so that

some artists - Bonnard or Klimt, for example - refused to divulge the

inner life which prompted their art.

The

resulting entities, made visual as pictures, may appear to viewers

intriguing,

even

inspirational, inviting a wish to share the artist's thinking behind

his painting. People discuss

my art and pretend to understand it, Claude Monet once said, as if it were

necessary to understand, when it is simply necessary to love.

Stanley too hoped that he

might persuade us to love

his pictures. A journalist who told him during an interview that she

found his pictures interesting

and was particularly impressed with

the precision with which he

painted bricks took the force of his

sudden fury: You wouldn't have

noticed the

bloody bricks, he

thundered at her, if you had loved my

pictures.

But to love fully is to understand fully,

'understanding' in this sense having no need of explanation. Although Stanley seldom found words to describe his

paintings after their completion, he was always willing to offer

sources for the impulses and

processes which had occasioned them, usually in vivid and

unexpected phrases. These accounts enable us, if we can interpret

them

accurately, to separate

out the

individual components of a picture, and to recognise the

contribution of each by locating its source in his mind.

But to love fully is to understand fully,

'understanding' in this sense having no need of explanation. Although Stanley seldom found words to describe his

paintings after their completion, he was always willing to offer

sources for the impulses and

processes which had occasioned them, usually in vivid and

unexpected phrases. These accounts enable us, if we can interpret

them

accurately, to separate

out the

individual components of a picture, and to recognise the

contribution of each by locating its source in his mind.

The procedure relies of course on the

extent to which Stanley left records of his thoughts, in his case most

generously. But then it has

the drawback of

evaluating each component in isolation,

whereas its contribution only becomes apparent if grasped in its

association with its fellows. Only when assembled together do the

components energise the picture and help to provide its dynamism.

So although individual components of

Stanley's art are laid out and discussed in sequence in the analyses

which follow, it is important to appreciate that it was

unlikely he

thought them up in quite such a formulaic way. As with most artists,

the

components emerged slowly over time, and then, in his case, gradually assembled

themselves in his mind as concepts,

or notions as he

called them.

It was to meet his genius's inborn demand to make these concepts visual that Stanley's mind evolved

instinctively - and even subconsciously at times - the systems proposed

in this website.

And what concept-systems they were when

rendered

in paint! Not only do they surprise by their originality, but the

procedure by which Stanley

managed them remained consistent

throughout most of his life. To fully appreciate the one, we need to

master the other.

Stanley as a cautious thinker

Stanley's formative years over the

turn of the Victorian era into the twentieth century spanned the period

when the traditional in art was being confronted by the new modernism. One part of him joyously embraced its freedom of expression, while another insisted it be

disciplined by the values of his upbringing.

The paradox is apparent

in many of his boyish drawings. In The

Fairy on the Waterlily Leaf,

for example, he draws a Cookham girl-friend as an all-too

substantial fairy, and poses her impossibly on a

floating leaf.

In Paradise, his

feelings for

the security of his Fernlea

home-life are honoured by a curious

collection of

boyishly-recalled domestic incidents.

Such

renderings, conveyed in

the

intimate minutiae of

the self-referential, intrigued

viewers, but also

puzzled them. When Stanley carried the process into

his more imaginative paintings by employing

biblical symbolism, viewers

split into those who admired him as a gifted 'religious'

painter, and those who could not fathom why he found it necessary to

limit his talent to

Christian example.

But for

Stanley the paradox did not exist.

He did not see his paintings conventionally. If we are

to see them as he saw them, we must get to understand his

thinking.

It is no

easy task, but the purpose of this website is to offer indications

which might help.

Let us begin by registering Stanley's

claim that there were two of him, each existing

simultaneously in a different life. One - his 'real' life - he referred

to as his down-to-earth or

secular

life. The other - his creative life - he called his up-in-heaven life, or his life

of special meaningfulness. The two

lives can be thought of as

corresponding to the terms 'present'

and 'timeless' as mentioned in the home-page. The terms physical and

metaphysical are used here in

the

same meaning, the metaphysical

often being expressed by Stanley in the metaphorical terms of biblical

paradigm or iconography.

Instead of Stanley's heaven, today's reader might prefer a phrase such as 'extended

reality'. Indeed,

the passing

of the years since his death in 1959 suggests that he should more

justly be viewed as a dedicated spiritual rather than a religious

painter - it is for me to go

where the spirit

moves me, and not to attempt to ally it to some known and specified

religion, he expostulated angrily

during his 1935 quarrel with the Royal Academy. 'Religious

painter' was an

epithet he

himself preferred for Tom

Nash (on the right of

the photo,

with stick) a colleague from student days who painted with a

Bible in one hand and my

ideas in the other. Stanley's God was mistily

defined - an echo of his creativity, perhaps,

in which his father Pa

played a substantial

rôle - and his

Christ was a very

personal concept, I can

imagine

what Christ might love and I hope it would coincide with what to me is

wonderful. If nowadays

the term heaven

has accrued notional, even sentimental, overtones, they have no place

in Stanley's art. There is not the least touch of sentimentality in any

of his work.

In common with the spiritual thinkers

and metaphysical poets

to whose writings he was so devoted from his student days,

Stanley was convinced that not only were his two lives intrinsically

linked - in my Flesh I see

God

- but could be understood as an

integral reflection of one

other. When mirror-imaged thus, the experiences in

his perceptual

down-to-earth life would become the comprehensions

of

his conceptual up-in-heaven life. When accurately connected, they expressed the 'truths'

he felt impelled to convey by means of his art.

The quest for these 'truths' or infinitenesses

as Stanley described them - the 'messages' of his major paintings

- took

place in

what he called his thought-world,

or that part

of his mind in which he tried to put his imaginative life into

order. Like most

artists,

he could record down-to-earth

feelings through his splendid landscapes and still-lifes, but if he

were to express the unities formed from his felt experiences he

needed to

interpret them through

more creative pictures.

Most artists employ

a personal free-floating imagination to

achieve

creative composition ('imagination' in this sense being defined

as the process of raising images in the mind.) But Stanley

recoiled from such usage. In

this significant respect he differed, for example,

from artists like

William Blake (with whom he is sometimes compared)

who dismissed the material

down-to-earth in his art and

raised his images from a disconnected

thought-world. Stanley admired Blake's radical poetry, but not his more

esoteric art.

It is important always to bear in mind that Stanley's image-raising

remained anchored firmly in his perceived down-to-earth experience. Only when he

was satisfied that his down-to-earth explorations were valid did he use images from them to reflect his metaphysical

up-in-heaven

concepts : or, to reverse the argument, his metaphysical

up-in-heaven pictures are, surprisingly, constructed from his everyday

down-to-earth imagery. The details

and figures in them are recognisable

as the actualities they were,

but in Stanley's conceptualisation have been re-shaped

into a metaphysical Stanley-world

or, in his potent phrase, have

become more intensely themselves.

It is to these highly personal renderings in his paintings, and not to

their apparently

factual visualisation, that he expects us as viewers to respond.

Stanley's

use of biblical symbolism

was an

instinctive response to this process. It provided a

frame - a paradigm - by which he could

keep his more abstract explorations

disciplined into a

coherent order. He did not so much see biblical events

as happening in Cookham, as is often suggested, but rather saw Cookham

as a familiar and loved background from which to image the

universalities he found so readily in biblical exposition.

Throughout his life Stanley exhaustively kept

up his exploration.

To help handle his

ideas, he maintained multiple memoirs,

notebooks, daybooks and letters. They run into millions

of

words. They

were a valued

possession for him. He

continually read and re-read

them. Occasionally

he tried to catalogue them into order, but

his

mind moved too quickly to adhere

to any system. Their

confessional

quality

can strike a reader as solipsistic, that is,

concerned self-centredly with himself. But such comments as the most exciting thing I

ever came across is myself or painting with me was the crowning of an

already elected king are not pretentious - to him they

were

simple statements of fact, and

a humbling astonishment, I have always looked forward to seeing

what I could fish out of myself, I am a treasure island seeker and the

island is myself. His

writings are egoistic,

but not

egotistical. For us

today,

their most important feature is that through them his

art becomes his mind unpeeled for us. Usually,

he once said, in

order to understand any picture of mine, it means taking a seat and

preparing to hear the story of my life.

When

judiciously connected, his writings tell the story of my life.

In so doing, they direct us to an understanding of his

vision.

Stanley

as a disciplined thinker

If Stanley's thinking was cautious, it was

also disciplined. It was always exact, if not

necessarily

intellectual in an academic sense. This claim might strike a reader as

surprising, given conventional views of his eccentricities, but coming

webpages will justify it. Its

precision gave order

to even the most esoteric and baffling of his creative paintings. It especially embraced an

Emersonian

respect for the

identities of things and their individual natures. This shows up, for

example, in

an incident in the 1920s when he was travelling with

friends by rail

from

Vienna to Sarajevo. As the train approached the Balkan mountains, one

of the

party opined that the

scenery is getting better now, only

to be put down by Stanley's terse reply that the scenery is neither better nor

worse, it is simply different.

The comment reveals Stanley's conviction that everything existed in its

own nature and that we should aim to understand it in that nature.

Our imagination should not be used to assign to it characteristics

it does not possess, unless we are quite clear what we are doing.

Moreover, if it is a living thing

it will instinctively seek a state of

perfection

in its

nature if, as a plant, it finds itself in its ideal growing

conditions

or as a creature, it is located where the maximum of food

and protection is available.

As one living thing among others, we humans also seek a state of perfection. But alone among nature we

are blessed (or cursed, the sin of Adam

and Eve?) with freewill

consciousness. We can

choose where our definition of perfection lies, as witnessed by the various world

religions or political economies.

Stanley, son

of a professional

musician and grandson of a

master-builder

responsible for erecting many of the big houses round Cookham, was

born

to an instinct for technical precision and to the

understanding that he had

to be

exact in his thinking if he were to reach the perfection

most

personal to himself

A more prosaic effect of Stanley's precision

of mind

was that perceived objects, events and people remained imaged in the

circumstance in which he first construed

them. Their image established their identity. If they changed

materially, the

effect

for him would be that they had become

different things with a new identity

which he had to master all over

again. For

that reason, although he accepted the inevitability of the flow of

life,

he was seldom comfortable with change until he had got the measure of

it. He did not enjoy the

disorientation of travel, for example, nor could he take an active part in

political or

social

affairs where change is endemic, even though his outlook was liberal.

The characteristic showed

up too in his disinclination to comment

critically on

the work of other artists. His

response was generally restricted to analysing their work to find meanings

in it which expanded his

experience (he only dismissed it if he could find none.) The trait was

particularly evident on occasions he

was invited to give teaching sessions at art colleges, where he seldom

felt had the time to grasp each student's outlook as fully as he needed to comment on it validly.

This precisionist aspect

of Stanley's

thinking applied equally to situations - physical or emotional - in

which he found himself. His first instinct on meeting a new

situation was to test its implications for his

artistic integrity. Would it further his creativity

or frustrate it?

The circumspection showed up in his personality as

fastidious

restraint and as

a

disregard for the shallow or the excitedly fashionable. This was particularly so of

his reaction in his earlier years to his normal male sexual urges, about which his

studiously chaste approach (he remained celibate until his thirties)

contrasted

with that of less

inhibited colleagues like

the

predatory Augustus John or

the impetuous

Henry Lamb. Only when Stanley could see his way into any new situation,

so

to speak, would he adapt his thinking or behaviour to it. He would then

dutifully

concur with its disciplines.

This austere approach Stanley applied even

to the inevitable matter of

death, his own

or others. His mother occasionally performed the village service of

laying

out the dead, and in their late teens the Spencer boys were sometimes

expected to

accompany

and assist her. To the onlooker, Stanley's undemonstrative acceptance

of this

conventionally traumatic situation could appear to verge on

indifference.

But it was not the deceased's physical extinction he mourned, so much

as their imaginative-creative loss, their 'soul' - Donne's for whom the bell

tolls. As will be suggested, he had other ways of dealing with

death's

emotional

impact.

Stanley's observed paintings

Stanley's instinctive

precision of

mind - or literalness of approach if one cares to see it in that light

- was reinforced by four years' study between 1908 and 1912 at the Slade School of Art,

part of University College London (he commuted by train each day from

Cookham.) It shows up particularly in his observed drawings and paintings.

In observed work, and especially in his many down-to-earth landscapes

and

still-lifes which he sometimes called his potboilers

because they provided ready income, he trained himself to record what he saw in

exact

detail, whether it was a

glorious tree in full blossom or a dismal heap of scrapiron in a shipyard (both had equal identity

in his

view.) Moreover he did so with intense absorption, displaying a notice

asking not to be

disturbed when

painting in the open.

Stanley's instinctive

precision of

mind - or literalness of approach if one cares to see it in that light

- was reinforced by four years' study between 1908 and 1912 at the Slade School of Art,

part of University College London (he commuted by train each day from

Cookham.) It shows up particularly in his observed drawings and paintings.

In observed work, and especially in his many down-to-earth landscapes

and

still-lifes which he sometimes called his potboilers

because they provided ready income, he trained himself to record what he saw in

exact

detail, whether it was a

glorious tree in full blossom or a dismal heap of scrapiron in a shipyard (both had equal identity

in his

view.) Moreover he did so with intense absorption, displaying a notice

asking not to be

disturbed when

painting in the open.

An anecdote about the novelist Barbara

Cartland's

daughter

Raine, then Lady Lewisham but later the Countess Spencer who became

stepmother

for a while to Princess Diana, illustrates both Stanley's intense

concentration and his accuracy in rendering detail. In April 1959 his

dealer had encouraged him, despite

his still being convalescent from a major cancer operation, to accept a commission to make a portrait of Lady

Lewisham, and he was, he complained, having difficulties with her eyelashes.

For her part, Lady

Lewisham, sitting to a preoccupied Stanley, could

not understand his unexplained spells of leaving his easel, coming

closely up to

her

face and staring long and hard into her eyes. Finally she plucked up

courage

to ask why. I am

counting

your eyelashes, he explained.

It can be cogently argued that Stanley's

instinct for graphic

exactitude, linked to that other dominant family characteristic, a

strongly humanistic

interpretation of Christian ideals, dovetails easily into his lifelong

devotion to the characteristics of Renaissance art. The pre-Raphaelite instinct

for exactitude similarly

prevailed for him, even when a task lasted

over a period.

If working on a landscape, he would

aim to revisit the scene at the same time of day and hopefully in the

same weather. If a portrait, no detail of the surroundings was to be

changed for the next sitting. If by mischance any were, he insisted

they be restored exactly.

Once absorbed into his

experience, a subject thus became a fixed, unchangeable entity for Stanley - eternal, in his vocabulary. Nothing of it could be removed or

altered after his initial received impression. When painting landscapes, any objects or figures which

might present themselves, however

lawfully,

would be

excluded. My

landscapes,

he once wrote, are places

waiting for their figures - that is, he could insert figures

only

if such figures had an eternal

association equivalent to that

which the landscape gave him, a situation which could occur in an up-in-heaven or metaphysical

interpretation, but not in an observed scene once sealed in memory. So

his

landscapes are empty of figures (see note on Southwold.)

None of this should be taken to imply that

Stanley's observed work was photographic. In fact, in one important

aspect, it was often unphotographic. Most artists look straight

ahead when composing their landscapes and begin their subject some

distance in front of their easel. But not so Stanley. To him, close-up detail

seen by looking down to his feet was as integral to a scene as detail

in the far distance. So

he saw no reason why he

should not only include it

but render it equally sharp. To the eye, or to a standard

camera

lens (which covers a normal eye field-of-view) this is impossible. Only

the close detail or the distant would be in focus. By making both

sharp, Stanley is in effect imposing a foreground wide-angle

perspective

on the expectedly normal eye view, a presentation which

can intrigue,

if unsettle, a

viewer.

Hockney later used the technique in some

of his acclaimed photo-collages, in his case with deliberation, but

instinctively

in Stanley's.

Stanley's

imaginative paintings.

Such precision of eye and mind worked well

for Stanley in

his down-to-earth thinking. But how could the

same precision, when carried into into his up-in-heaven thinking,

be expected to convey

the

infinitenesses of his conceptualisations?

The answer will take us into the heart of

Stanley's creative imagination. The first step is to appreciate the

significance of another personality characteristics which so defined

his

approach to

art, his prodigious visual memory.

All artists use memory for their

purpose. But

there must be few, if any, who used it Stanley's way. It was the

well-spring of those paintings which he regarded as his important work,

his

imaginative compositional 'up-in-heaven'

pictures.

In an observed painting he was able to image his feelings solely in

the

setting, the location of the scene. But in an up-in-heaven picture he

had to image his feelings

in both the setting and the 'message' of the picture. It had to

convey the concept he wanted to express which might or

might not have obvious relevance to the scene through which he chose

to depict it.

We need a telling adjective to

describe

the character of these paintings.

The adjective 'conceptual'

would fit, but it is already in use to describe a

different form of postmodern art. 'Conceptualised' might do, as would

'compositional', except

that as

adjectives they lack the

element of

vision

so important to Stanley in his art.

So throughout this website the

term visionary will

be used to refer to these imaginative paintings, with

the

word

'vision' to be

understood in its meaning of

reaching out to some glimpsed ideal, and not in its

eidetic, Blakean, meaning of something illusory, fantasised, or

allegorical.

Stanley's approach to visionary work.

For Stanley, the process of evolving a

visionary painting worked as

follows.

A scene, idea, or event

which caught his attention (a 'light-bulb' moment,

however minor) would settle into his memory as an image prompting the

possibility

of comprehending a

new concept.

The comprehension would not always be

immediately clear, but if he could later connect it with other relevant

memory-images, he might be able to assemble a composition

which would clarify the

concept. If he had time, he

would make a quick sketch of the experience.

Because the 'light-bulb' moment - the perception - happened to him in the

real world, that is, in his down-to-earth life, it could raise emotions

for him. They might be of joy, of

exultation, of bewilderment, of anger or even fear. But unlike most artists, Stanley preferred not to record their

immediate impact or emotion as, for example, Munch

used a

sensation on a fjord walk to paint his versions of The Scream,

or Picasso his Guernica

from anger at news of the bombing there. Instead, Stanley kept the

memory of the experience by him in the hope of later finding the means

of transforming it - and importantly, redeeming any hurts it

had given him - into the

reassuringly-tranquil universal feelings of

his

up-in-heaven world. Always

highly

sensitive to atmosphere, his instinct was

to

transform the

actuality-plus-emotion of

the experience into a state of

imaginative thought.

The resulting

picture-making process thus became one of metaphysical transformation

or

metamorphosis.

For Stanley the most

significant metaphysicalities

were those which reveal the communal

or coming-together

aspects of our existence, those areas of life and thought in which we

are

in his term liked with our fellows, that is, made 'alike' (conscious of

our collectivity or universality)

while

at the same time retaining our individual identity. He saw our altruistic instinct to be liked with our fellows as a

product of what he called the Love of God, manifested in each

of us by our desire to love

in all its varied aspects.

The polarity between our universality (Freud's 'superego', indicative

of our imaginative desire

for the collective) and our self-regarding instinct

for

our own identity (Freud's 'id', which tends to settle for the prosaic)

formed the kinetic of much of Stanley's

most valued visionary art. Whenever a picture had successfully

replicated a down-to-earth experience in an up-in-heaven form for him,

then he

felt it

had revealed a comprehension as a part, even if

only a microdot, of our universality.

This can help explain why Stanley thought

of himself as two different people. However joyous, exultant,

bewildering or infuriating an experience was in his practical everyday

existence, he had the gift of seeing it at the same time

as offering universal

(up-in-heaven) insight. He

conveys this

duality in some paintings by inserting himself as part of the

experience. Or else he shows himself - not necessarily in his own

person but in some equivalent

form - as undergoing the experience which is being

transformed

by his picture from down-to-earth to up-in-heaven.

Making the switch

The key to making the switch from the

prosaic impact of a down-to-earth experience into the majesty

of an

up-in-heaven comprehension lay in Stanley's use of memory, and

especially in his powerful episodic

memory.

He would begin by quietly settling to see if he could recall past experiences in which the feelings

corresponded to those needed for the new

project.

He came to call these recollections

his memory-feelings, and the procedure contemplation - the Spencerian equivalent of

Wordsworth's emotion

recollected in tranquillity. Being recalled

from memory, they were eternal for Stanley (that is, he saw them as permanently available in his

mind even if only thought about when needed.)

Sometimes Stanley's contemplation was

sterile, or would offer

only inept - what he called incompetent  -

memory-feelings, and he would complain bitterly of

frustration. His recalled memory-feelings were truly effective when

they replicated for him creative moments associated

with aspects of love

in his spiritual meaning.

-

memory-feelings, and he would complain bitterly of

frustration. His recalled memory-feelings were truly effective when

they replicated for him creative moments associated

with aspects of love

in his spiritual meaning.

When such contemplation

generated apposite images, Stanley

would record them as detailed

pencil drawings, or sometimes as ink-and-wash sketches to test their

compositional tonality. He generally used Imperial-size

(30 ins x 22 ins) paper for this task, and left many

thousands. If any did not convey quite the feeling he wished, he would

set

them by until more suitable examples cropped up. But on

those he decided to use he

would pencil a grid with a

draughtsman's

accuracy in readiness for enlarging it to a

(usually) primed

canvas either as the basis of a single painting or as a component in a

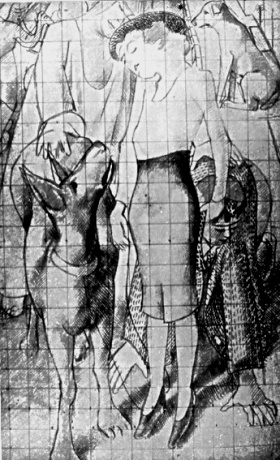

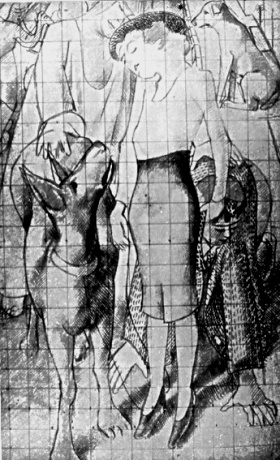

composite work. The attached drawing, one of a series called Patricia

with Dogs, is an example.

Stanley's

memory-feelings.

The importance of his memory-feelings in

Stanley's visionary art cannot be

over-emphasised. They were more than a mere jumble of recollections. His mind worked so associatively that while keeping

each memory-feeling clear-cut (eternal),

it continually chain-linked them as strands

in

a pulsating web of metaphysical

significance for him

(discussed when we

reach the webpage on his Vision.)

This web of thought was so complex that when in

1938 he was approached to write his autobiography, he was adamant his

book would have to take the form of a stream-of-consciousness in which

all his life's memories would combine and

associate. He would allow nothing to be omitted or edited

out, an

uncompromising attitude

which reflected his conviction that everything that had happened to him was

linked, and that nothing

of it could be

stressed as more significant than any other. On that reef the

publishing venture

foundered. Stanley remained unabashed and impenitent.

However, we can now we can

see why Stanley's

writings are

so helpful in understanding his visionary art. If we can track down

from his memoirs the memory-feelings he used, we can

begin to appreciate what they meant to him at the time of their

origin and so gain a clue to their intended function in

establishing feeling in the new project. Examined now, the memoirs are so honest in their

self-revelation that they need to be read with empathy. There was a moment during Stanley's last

illness when he wondered if his writings should be burned : mercifully

they weren't. But they can

be cruelly misinterpreted - as

he suspected they might - and on occasions

unfortunately have been.

Resist such sensational 'exposures'. They

can fascinate, amuse, even shock. They often make good after-dinner

yarns. Stanley never greatly minded, provided they did not promote the

scaffolding of his paintings in place of the edifice (a particular

public temptation, it seems, when dealing with their sexual content.)

But art-wise such comments, however titillating, are vapid, because

they are restricted to his down-to-earth life, and for him that part of

his life had no meaning if not set against his

up-in-heaven life. Whoever seeks them out but fails to make that

connection is wasting his time - and ours - as a critic of his art.

Stanley's large

visionary paintings.

For his large composite visionary

paintings -

invariably those which had major significance in his outlook -

Stanley would kaleidoscope

his

selected drawings into a

master-composition. Once satisfied with this

master-composition, he would

use his pencilled

grid-system

to transfer it, section by section, to a full-size canvas ready

for painting. These

assemblies could thereby

became

'modernist' complexes of multiple or

mixed perspectives, and his adjustment of them in the interests of

overall composition, achieved

instinctively as he worked, was always consummate. The task was

usually undertaken in such

high creative

excitement that he would

refuse or postpone uncongenial social

invitations in order to work undisturbed for hours or days at an end until he

had achieved the effect he wanted.

The

whole process was so important to Stanley

that when it operated

effectively, he felt transported into a state of happiness,

that is, to a state of such creative imperturbability that the

physical problems of existence, however pressing, had no influence. The effect was sometimes such that he could continue

producing up-in-heaven

paintings while apparently behaving in a contrary way in his down-to-earth

life. But when both lives coalesced, his happiness was complete. The

supreme example of these

states was related by

him to the creative ecstasies

he had experienced in his adolescent days at home in Cookham. He knew

them as his Cookham-feelings.

For him it was the glorious period of his most

inspired

exploration and his most fruitful contemplation. Its impact coloured

the whole of his life.

The final

application of paint - often postponed for weeks, months or even years

- was

normally done

thickly in dark tones, but, when

time pressed, so

thinly in

light tones that the

pencil lines showed

through. Being right-handed, Stanley usually worked

diagonally from the top left corner to avoid smudging. He

knew he was a

great

artist, but never claimed to be a great painter in the

traditional sense, although his techniques were invariably adequate for his intentions.

Throughout his life Stanley's

compositional procedure

was remarkably consistent.

Visionary projects sourced from his memory-feelings

were always

studio-painted. Imagery drawn from the memory

component

would be adapted for

the setting of the picture,

and

would normally reproduce

a location where Stanley had undergone the experience (we have to use

qualifying words like 'usually' or 'generally' or 'normally' because

inevitably there are modifications in detail.) If the experience was

not based on an actual event, Stanley would select a location he felt

had an appropriate association. In his early visionary paintings, the

chosen

setting was often painted with considerable exactitude, at times almost

like one of his observed landscapes. This would be so even when he was only a short walk

from

the location he was using to set his scene. Sometimes he would go to the

location

afterwards and pride himself on how accurate his memory had been. But

in adapting the memory-location for his purpose in the quiet of his

studio, subtle differences in perspective and

emphasis would occur. Sometimes

he

would add associative details from other locations if he thought them

relevant.

The feeling

element of the memory-feeling,

on the other hand, would be sought by augmenting

the setting with images of remembered objects and people, often physically unrelated,

but which recalled emotions Stanley

associated with

the overall concept he

wished the picture to convey. Since

these images too came

from Stanley's memory, they were eternal,

and because their now eternal

'atmosphere' matched the

'eternal' atmosphere

of the setting - unlike

his procedure in

observed landscapes where only the location was 'eternal' - they could be

introduced as pictorial forms.

This applied especially to the people

- figures -

he could now depict.

The figures in Stanley's

visionary paintings form an

integral part of the concept. His precision

of mind - or lack of inventive 'imagination', whichever one prefers -

meant

that normally they

reproduced real people he had seen or known. In

this respect he acted like a playwright or novelist who, needing to

motivate his story through the use of characters, creates them by

modifying the personalities of people he had come

across. Sometimes the

figures represented the original people of the observed scene or

experience, but especially in his later paintings he would happily

import from his memory people

who held associations

appropriate to the

feeling he wanted. When he needed legendary or more symbolic figures,

he liked to persuade people he knew

to model for them, so that a 'real-life' Hilda Carline stood in for the

figure of Christ in his

1923 The Betrayal, or Patricia Preece for the

Virgin Mary in his 1934 The Crucifixion.

Because Stanley's visionary paintings were

constructed to convey a concept

rather than depict a narrative, his figures were not meant

to be viewed as 'real'. They were essentially metaphors in his

up-in-heaven

interpretation of the emotion. So he would modify them from their

physical

originals and transfigure them into what he called shapes.

Sometimes, like most

painters, the forms and

attitudes of his shapes could

be influenced by those used by

past

artists, especially those from the mediaeval and early renaissance

period

with which he was so familiar.

Thus Stanley's figures emerge on the canvas in

their

transfigured form. His

down-to-earth feelings about

them might or might not have any relevance. For him, they were no

longer in their down-to-earth personalities. Yet for those who knew

them in real life they invariably remained recognisable as the actual

people they were, in the

same way that his settings are generally identifiable.

There were times when Stanley's feelings

about an experience or concept grew so intense that he could

match

them visually only by exaggerating his shapes beyond normality. He

would

find himself subconsciously elasticizing

them and the spaces between them - in other

words, distorting them. Such

figures, scorning spatial subtleties and seemingly shouting, 'Look at me!' - as no doubt they did to

Stanley on the

day

he conjured them - frequently force

themselves boldly on the canvas and thus take on their so-called

'funny' appearance. They

and their detail become more quirky to the

eye,

and the

paintings acquire the

character of a 'Stanley Spencer'. As a

general rule we

can say that the more distorted the detail in a picture, the more

intense the

feeling (and often, unfortunately, the more bizarre and 'ugly' its

imagery to an uncomprehending viewer.)

Because of this shape-changing, Stanley found

it difficult to explain his figuration without sounding odd or

embarrassing their prototypes,

and usually refused to do so. But more important was the fact that

his figures in their new up-in-heaven shapes became more real to him

than

in

their down-to-earth forms. He used to say that his picture people were my loves. They populated his

thought-world and were there permanently. He had created them. They were to him his children. Like

the paintings in which they appear, they were the product of his

creative loins, so to

speak, and like real

children, once brought into existence took

a life of their own, becoming independent entities from him but now separate from him. Moreover, unlike

human children, they could never change their form or suffer decay.

They were eternal. In the biblical terms imbibed from Pa, he, Stanley, as a

metaphysical Stanley-Christ had symbolically

resurrected them through

his

art into a perfection

fashioned from his comprehension. He had put them in a setting, a

Paradise, of his making

where they were granted immortality. In the

rolling biblical phrases of St.Paul, the corruptible had been made

incorruptible.

Stanley's unifying

mind

To briefly

recapitulate. So far in this webpage

attention has been drawn to the dialectic of Stanley’s dual lives - his

perceptual down-to-earth and his conceptual up-in-heaven - as they

reflected

one another to convey

individual identity merged into

universal perfection. Whereas most artists express such feeling through highly-imagined form, Stanley was

curbed in its use by his

innate caution

and disciplined precision of thought. So to achieve

a

comparable effect he used contemplation,

going back

in his mind to earlier states

from which he retrieved past detail - memory-feelings - which matched

the emotion and atmosphere

he felt he needed for the new painting. The

memory component provided

the picture's setting, and the feeling

was conveyed by the shapes

of the associated detail, mainly figures of

people.

So far, so good. But then Stanley faced the problem mentioned

earlier. Viewers

coming across one of his

visionary pictures

for the first time could suppose it to represent a narrative situation.

Even those perceptive enough to realise that the detail in the

painting was highly personal to Stanley could be

disconcerted by its apparent irrelevance. It

would not immediately be clear that the picture's detail was

intended to

be linked by equivalence of feeling,

and not by that of time,

place or situation. Nor might first-time viewers appreciate that the

apparently factual imagery was intended to be metaphorical and in

process of undergoing

transformation into an up-in-heaven. How could Stanley, in attempting

to

explain a picture, put that

into words? He couldn't, and

usually didn't try, so that whereas he was eloquent about the planning

of a project, he was generally silent afterwards about

its

accomplishment.

Sometimes, if pressed, Stanley would politely try to

help viewers by outlining the metaphysics

behind a painting, but

then his

listeners would often find themselves unable to grasp a

connection between the visuals he described and those they saw.

The result would be viewer

mystification, or even dismissal. Misinterpretation of Stanley's

paintings haunted his

life, and

can still.

Stanley's

difficulty was that his compositional procedure,

effective though it was at picture-making, appeared to deprive his

paintings of the

connection between the

actual and the invented which

unfettered imagination so

generously

offers other artists. To amalgamate

his apparently disparate detail into a coherent unity, Stanley needed to

find a dynamic means

whereby it

could

be

interpreted in its associative

aspects. His remarkable

solution

was to use his instinctive

process of reflection or mirror-imaging

or reversal

by turning it into the forms of visual counterpoint.

Stanley's

counterpoints in operation

Stanley's use of the counterpointing

principle is apparent even in early work, such as Apple Gatherers which

can be interpreted as based on the 'separateness' of the two sexes

coming into

the mutuality - 'unity' - of adult understanding, and in Zacharias

and Elizabeth where the separateness of husband and wife is

gloriously 'married' into their cosmic unity as Elizabeth announces

to the disbelieving Zacharias that she is to give birth to John the

Baptist.

But Stanley's

counterpoint usage is especially evident in his 1912 The Nativity

(University College, London.) We can use it as a template.

The title - the Nativity - was the subject set for the

Slade Summer Composition Competition for 1912. The students were free

to

interpret it as they wished. In Stanley's version, reproduced here in

black-and-white, the right background shows a chestnut tree ringed with

its blossom 'candles'. In the top left background, a meadow slopes down

to

the Thames (below view), and beyond are the wooded slopes of Cliveden.

It is apparent that

Stanley's picture is

not a direct re-working of the traditional original. The season is

spring or early

summer. Patently the concept - the 'message' - sources from an amalgam

of Stanley's feelings about his Cookham locality, his depiction of

nature,

and the annual period of animate rejuvenation.

Unravelling The

Nativity .

The figures in the painting meet on a path,

recognisably Mill

Lane in Cookham. The location shows the spot where

the public lane ends at a detour round one of the big houses of

Cookham and becomes a path through a private park.

In Stanley's day there was a right-of-way access across the park to a rowboat

ferry across the Thames

to the grounds of Cliveden. Stanley's choice of the setting is

intriguing in that it images the point on the Lane where the switch from 'public' to 'private' reflects a change in atmosphere,

to use Stanley's

terminology, always suggestive in his visionary

art as the two 'separates' of a potential counterpoint.

If the purpose of a counterpoint is to

show a 'marrying' between

'separates' - a unity from duality - it will help the

viewer if it contains imagery indicating the separation point or

'barrier'. In

Stanley's early paintings the barriers were sometimes symbolised by the

property walls which so affected

his boyhood (Zacharias and Elizabeth)

or by the steep banks of the Thames where he swam, as in John

Donne Arriving in Heaven.

In The Nativity a fence

of a design common then in Cookham gardens marks the

division between the 'public' and 'private' sections of the Lane. There

seems to

have been a metal railing there originally, no doubt with a gate or

stile, but Stanley has imported his garden fence from

some

other

Cookham spot as a substitute 'barrier'.

To the right, in the 'public' or

'universal' part, is the

Holy Family, the

up-in-heaven group, the subject

of what will become his fugue.

To the left, in the 'private' or 'personal' part, are two couples

embracing. They are the

down-to-earth group, the episodes.

They make sense if we surmise they are lovers

modelled on Stanley's older siblings who had recently wed or were about

to do so. Visually the separateness

of the two groups is further emphasised by distinction of costume.

How then does Stanley 'marry' them? He

does so

by asking us to see the barrier as metaphysical, not as the actual

metal railing it probably was. When we, the

viewer,

comprehend - or at least glimpse - what the painting is 'about', then

the

garden fence, the barrier, will 'disappear'. We will have been

transferred into Stanley's

thought-world.

We will have expanded a 'private' percept to 'public' concept. We will

be 'listening' to

his fugue. So let's follow his

associations.

In real-life Stanley's brothers and

sisters were, like

himself,

well-versed in the Bible.

Ma, a convinced Methodist and local secretary of the British and

Foreign Bible Society, insisted on daily Bible reading by her children

when young. So they were all

familiar with

the meaning of the Virgin Mary in her Christian rôle as

Mother of God.

But, through Pa's more searching humanistic outlook, they also knew

her as emblematic

of the Creatrix,

the archetypal Great Mother.

So it is odd that here, in Stanley's

painting, the lovers do not see Mary, although she is gazing at them

intently (one of his cousins, Amy Hatch, was persuaded to model for

her.) They cannot recognise

her beyond the fence because Stanley is presenting her as an abstraction;

that is, she represents an invisible entity in our conceptualisation, counterpointing his corporeal

brother and

sister on the other side of the fence. He

is

reinforcing the prison-wall

tapping he so desired in his outlook and metaphysically

morphing 'private'

personal feeling into

collective 'public'

concept -

the basic process of his visionary work.

Since Mary is an abstraction, most artists

might depict her

imaginatively. But we know that Stanley cannot or will not do

this. She must somehow be given a palpable down-to-earth form to match

that of his siblings and the

rest of the physical detail from which he has constructed his

composition. So he tells

us elsewhere that he has given her the form of a public monument,

a statue to someone important standing in a public place. This maybe is

why

she appears so masculine, for such statues in Stanley's day were mostly

of martial

or political heroes. His reasoning is that as a public statue she

offers a

characteristic of most monuments in that they

are permanently there but unnoticed by those who pass preoccupied in

their

down-to-earth lives. In other words, in the ethos of the painting she

is a prototype for

something ethereal or spiritual - the recurrent eternal of the visual fugue he

is composing -

which, like the air we breathe,

is always accessible as part of our existence, even if only intermittently

thought about. If we can begin to appreciate the implications of

the

imagery Stanley is using here, we can begin to draw near the heart of

his

painting.

There is, however,

one figure in the composition who can see Mary and the Babe, a

strangely ecstatic figure kneeling by the fence in worship. Stanley

once described

him as the third of the Three Wise Men who are worshipping baby Jesus

(the lovers no doubt represent metaphysically the other two.) For that

figure, the

barrier does not exist. The figure must surely be Stanley himself in a

visually odd - and therefore pinpointedly significant - up-in-heaven

persona.

It is noteworthy that Stanley even at a

young age had already realized that few viewers or questioners would

understand his ideas unless he set them in a form within their

experience. The Three Wise Men they could grasp. But if he said the

kneeling figure was himself in awe of the spiritual atmosphere he

discerns beyond the fence, most would probably have thought him

'peculiar'. So

it

was less wearing to prevaricate. The habit was to persist throughout

his life.

By means of such images we at last arrive

at the

threshold of Stanley's thought-world (as we are expected to do in all

his visionary pictures.) The 'marrying' in his counterpoint has taken

place. Through his

assembly of relevant down-to-earth percepts, the

circumstantial in our lives is revealed as

linked metaphysically to the eternal in our existence. His

concept has been transfigured into the up-in-heaven for him -

and,

hopefully, for us.

Stanley does not tell us in his writings

what was the 'master' experience or notion from which the painting

sprang. The picture - the comprehension - originated as an

epiphany in circumstances personal to himself. Its specific

associations lie outside

our own background, but the whole is offered in the hope

that we might be able to recognize the message from within our own

experience.

Because each viewer will interpret the

concept - the 'message' of the painting - from his

own experience and in his own way, there will be as many 'meanings' to

the painting as there are viewers who respond to it. But the meanings

will tend to cluster into categories which we can call, as Jung did, archetypes,

because they have the property of illuminating the evolutionary

emotions, feelings and comprehensions common to the universality of

humanity.

Perhaps the imagery tells that the

lovers' unions are part of cosmic destiny, the animate will to

procreate and renew. Or maybe it tells that human love and physical sex

are sacred and that marriage metaphysically reflects the historic unity

of dual gods into a monotheistic unity, a single Godhead.

Alternatively it may offer no 'message' at all, but a viewer will be

intrigued by the superlative composition of

the painting, or by the sense of mystery it conveys. In fact it can

provide

whatever meaning we wish to find in it, surely the sign of a masterwork.

Subconsciously Stanley has superposed so

many levels of meaning - as he did in all his visionary paintings -

that although we can deconstruct the imagery by the linear thought

processes we use to define our down-to-earth lives, we can best

distinguish its levels by using a vertical up-in-heaven thought process

which invokes our feelings from our

experience, our intuition. Reliance on intuition rather

than intellectual logic became a major element in Stanley's artistic

thinking and output, as will again be apparent in coming webpages.

Stanley's retrieved associations - his memory-feelings - are

ingeniously used to construct the painting. For example, he felt the

need to convince

us that we should see his image of Mary as having the characteristics

of

a monument. Statues have plinths or pedestals, so in his precise mind

she

cannot be a monument without one. None existed at that spot in Mill

Lane.

But at the river end of the Lane path, where at that time it met the

ferry,

the ferryman had strengthened the bank with sacks of mixed sand and

cement

left

to dry to concrete. What better association to import for Mary to stand

on,

seeing that the ferry was called My Lady Ferry?

The watermeadow by the Thames seen in the

picture (one of young Stanley's adored Cookham marsh meadows) was in earlier

times flooded in winter but lushly grassed and

wild-flowered in

summer.

The two tall stones Stanley shows (gone now) formerly marked allocated

village

hay lots (the Haywarden is still a fossil Cookham parish office.) The

Lane had such a powerful meaning for Stanley that he once took the

unexpected step of 'marrying' himself

to it by burying a tin of his precious drawings there (where, alas,

enthusiastic

tries at metal-detecting have failed to find it.)

Was Stanley perhaps using his 'marriage'

of himself

and the Lane to honour an ancient Rite of Spring, linking it with a

highly

personal experience which overcame him there?

It is possible. Joseph on the right

(imaged from

a drawing Stanley made of a Slade male model) is shown as a virile

young

man, not the old man beyond the possibility of fatherhood who would in

traditional

terms have been more accurate. Some commentators have seen him derived

from

the image of Mercury in Botticelli's comparable Primavera, others

as the figure of Joseph picking fruit in Gerard David's Flight into

Egypt.

He is, said Stanley, doing

something

to a chestnut tree. Stanley later confessed his boyhood guilt about

defying Victorian prohibitions and yielding to masturbation, his woeful habits as he called them,

perhaps for their physicality but also because they dredged up fantasy

associations which seemed to him to have no relevance to the stringency

of his thinking. Maybe he was using that detail in the painting to

exculpate his bewilderment, or in his

words, to help redeem it

into his up-in-heaven thought-world.

Look, for example, at the kneeling figure

of Stanley in his thought-world. He is almost masked by a tall plant.

It appears to be a sunflower which, because of its profusion

of seeds, can

traditionally represent the

fecundity of the sexual, but which is also known for its habit of

turning to face the sun. In Stanley's picture it faces the

Baby Christ, a figure which he

mentioned in

one account he came to as an afterthought. It is

entirely possible that

already

in these early years Stanley was touching on one of his links

between Christ - today's conflation of the ancient Sun God with light

in the form of the

Light of

the World - as a symbol of the

'up-in-heaven' in

our existence, with the sexual instinct as the 'down-to-earth' which

sustains it, a theme he was to develop powerfully in later paintings,

such as Sunflower and Dog Worship.

In this Nativity painting the

sunflower is not yet fully grown. Is Stanley telling too of his

uncertainty

about the implications of his adolescent urges? If so, his lovers, his

older siblings, are entering a state of awareness as yet denied his

youth. He is still an onlooker, with an over-the-wallish feeling about

their anticipations. Their sexual expectations are sanctioned by the

universality of

humanity. They are holy.

But are his? Could this be yet another of

his personal confusions awaiting elucidation?

The mind begins to reel with the profusion

of implication. No single layer of meaning can be more significant than

any other. Each chases another's tail. They begin to intermingle in our

minds into a rotationary form, a poetic thought-form once called a

vortex. It is

as though we are being battered by a tempest of ideas and feelings.

Then, with luck, we reach a comprehension. The effect, if we manage it,

is as if we had reached the calm eye at the centre of a storm. All

around us is the roaring of the whirlwind, the vortex, but we are

suddenly becalmed into the

peace of an understanding. We have reached that moment when the two

dynamic

themes of Stanley's counterpoint achieve for us what has felicitously

been

called the 'stillness of synchronicity'. The artist and his imagery

disappears, and only his product, his concept, emerges in our mind as

pure emotive sensation, often beyond the power of language to

contain.

The experience provides us with

dramatic catharsis, a momentary glimpse of timeless universality, an

aspect

of the identity of God for those who see it in that light.

There is a salutary lesson here in our

analysis of Stanley's method. Although detail is skilfully used for

compositional effect in his visionary paintings, little of it is

random or inserted for infill.

Nothing can be ignored.

Every detail contributes.

For a ninteen-year old art student such a

combination of art, poetry and drama was a remarkable achievement. It

won him a deserved Slade prize.

As with all geniuses, Stanley appeared on

the artistic stage already fully-formed, so to speak. And like all

geniuses, he continued throughout his life not so much to develop his

early promise as to amplify and fulfil it.

Stanley's instinctive

precision of

mind - or literalness of approach if one cares to see it in that light

- was reinforced by four years' study between 1908 and 1912 at the Slade School of Art,

part of University College London (he commuted by train each day from

Cookham.) It shows up particularly in his observed drawings and paintings.

In observed work, and especially in his many down-to-earth landscapes

and

still-lifes which he sometimes called his potboilers

because they provided ready income, he trained himself to record what he saw in

exact

detail, whether it was a

glorious tree in full blossom or a dismal heap of scrapiron in a shipyard (both had equal identity

in his

view.) Moreover he did so with intense absorption, displaying a notice

asking not to be

disturbed when

painting in the open.

Stanley's instinctive

precision of

mind - or literalness of approach if one cares to see it in that light

- was reinforced by four years' study between 1908 and 1912 at the Slade School of Art,

part of University College London (he commuted by train each day from

Cookham.) It shows up particularly in his observed drawings and paintings.

In observed work, and especially in his many down-to-earth landscapes

and

still-lifes which he sometimes called his potboilers

because they provided ready income, he trained himself to record what he saw in

exact

detail, whether it was a

glorious tree in full blossom or a dismal heap of scrapiron in a shipyard (both had equal identity

in his

view.) Moreover he did so with intense absorption, displaying a notice

asking not to be

disturbed when

painting in the open.  But to love fully is to understand fully,

'understanding' in this sense having no need of

But to love fully is to understand fully,

'understanding' in this sense having no need of  -

-